|

Dr Tom Cromarty Editor Interests: Paediatric Emergency Medicine, Medical Engagement and Leadership, Simulation, Quality Improvement, Research Twitter: @Tomcromarty |

Welsh Research and Education Network

WREN BlogHot topics in research and medical education, in Wales and beyond

Dr Celyn Kenny Editor Interests: Neonates, Neurodevelopment, Sepsis, Media and Broadcasting Twitter: @Celynkenny |

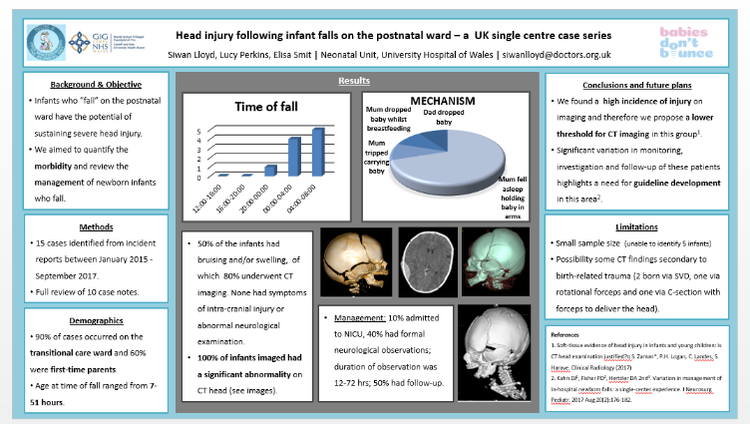

3rd-5th January 2018, Siwan Lloyd I had the pleasure of being able to attend the British Paediatric Neurology Association Annual Conference this year held at King’s College London. Despite a horrendous viral illness over the festive season which left me with significant post-viral fatigue, I managed to catch my early train to London on the 3rd of January (and had the pleasure of travelling first class in view of my tardiness in buying the ticket resulting in the first class ticket being cheaper!). Loaded up with free coffee and biscuits from the first class carriage, I arrived in London just in time for the first session. The venue was great, close to Waterloo Bridge, and there were beautiful views of the city to be seen in the evenings when crossing the bridge to attend the social events. The conference had a packed programme full of interesting talks, clinical practice sessions, e-posters and symposia. One of the highlights included the opening talk by Dr. Charlie Fairhurst who discussed the creation of the NICE guideline for Cerebral Palsy in under 25’s in which he emphasised the importance of treating pain first and foremost because if a child is in pain, there is no point in complex interventions to improve their mobility/social interaction because the pain will hinder the child’s participation. Patients with Cerebral Palsy are particularly at risk of pain from numerous sources (e.g. orthopaedic/muscular problems, GI dysmotility, pressure sores, dystonia etc. in addition to the usual causes of pain that anybody can experience). I felt that the talk also provided a very important reminder of the need for holistic and multi-disciplinary care. There were multiple presentations throughout the conference on current research ongoing in neurological disorders (including neuro-inflammation in psychiatric disorders, antibodies in neuro-inflammatory and demyelinating disorders, neurogenetics etc.) which really made me appreciate the rate at which our understanding of neurological disorders is advancing. There were also sessions on Neuroimaging including advances in fetal neuro-imaging (talk given by Prof. Mary Rutherford) and advances in PET scanning particularly in guiding epilepsy surgery. On the first day, I attended a workshop on Childhood Sleep Disorders run by the tertiary sleep service at Evelina Children’s Hospital, which involved learning about methods of sleep assessment (including polysomnography, actigraphy and sleep diaries). Pharmacological therapy including melatonin and clonidine (for fragmented sleep) were discussed. We also discussed potential contributors to sleep fragmentation (e.g. pain, seizures, obstructive sleep apnoea) and also discussed basic sleep hygiene advice and psychological interventions to help with behavioural insomnia. On day 2, I attended a workshop session on early epileptic encephalopathies and the emergence of underlying diagnoses related to epilepsy gene panels where the indications for genetic testing were discussed. We also discussed when a referral to a clinical genetics service is indicated and the common genetic mutations now being identified on epilepsy panels (SCN1a, SCN8a, SCN2a, KCNQ2, PRRT2 etc). On the third day, I attended a workshop on movement disorder emergencies including how to manage status dystonicus. This was something I had never come across in clinical practice and therefore was a very useful session highlighting the management including pain relief, dystonia medications, checking CK, strict fluid management. The session also discussed common mutations causing dystonia (including DYT 1, PANK2, RRT1, TOR1A) and also discussed surgical management options including deep brain stimulation and pallidectomy. This year’s conference used an app instead of the usual printed programme. The app allowed you to formulate your own personal programme and came with alerts to indicate which talks were about to start. During talks, you could also write notes on the app which were then linked to the talk. At the end of the conference you could then download all of your notes. There was also an option to ‘chat’ with other attendees during the talks (though I didn’t use this feature as I felt I didn’t have anything very intelligent to say as many of the topics were completely new to me!). During the conference, I presented my poster on head injuries sustained following infant falls on the postnatal ward. The poster outlined the findings of a case series of infant falls in UHW between January 2015-September 2017. We found a high incidence of injury on CT imaging in these infants and therefore we propose a lower threshold for CT imaging in this group. We also found significant variation in monitoring, investigation and follow-up of these patients highlights a need for guideline development in this area. I am now planning to expand this project to a multi-centre WREN project collecting data from other units across Wales to gain more insight in to the scale of this problem and how cases are managed elsewhere across Wales.  Dr Anne-Marie Proctor presenting her poster. Dr Anne-Marie Proctor presenting her poster. I was very pleased to see that two other Wales Deanery Trainees also had posters to display at the conference. Anne-Marie Proctor with her poster on Improving EEG investigations: Child’s Play? This poster presented how extension of a child-centred approach to EEG (including play therapy and flexibly timed investigations) to a second site in ABMU improved EEG success rates. Qumrun Nahar also presented her poster on the delivery of Botulinum Toxin Injection for Children with Spasticity: a Service Evaluation Project in Pembrokeshire, West Wales which showcased the service model of Botulinum Injections delivered in a rural DGH. This year’s conference displayed all of the posters as e-posters which meant that poster presenters were given a 3 minute slot to present their poster as part of a powerpoint presentation in a designated room. All presenters had 2 minutes to present and 1 minute for questions. Numerous poster presentations were running in parallel. The positive side of this was having an allocated time session to present your poster, and then you were free to listen to the other posters being presented with no obligation to stay standing next to your poster. The down-side was that because of the parallel sessions it was easy to miss out on seeing another poster that took your interest. For example, unfortunately I couldn’t attend both Anne-Marie and Qumrun’s poster presentations and was very sad to have to miss out on seeing one completely. There were also some posters which I felt could have generated much more than three minutes’ discussion and it was a shame to be limited to that timescale (some of the presenters struggled to describe their poster in any sort of detail in only 2 minutes!). It was an interesting and innovative way to display posters and it will be interesting to see if the idea is taken up at other conferences.

I was absolutely exhausted at the end of the three days, but know that I have learnt a great deal that will improve my interaction with children with neurological disorders, their families and the wider MDT. You can download the BPNA app which has further information on upcoming BPNA courses and events. And if you have an interest in Paediatric Neurology I would thoroughly recommend attending the BPNA conference next year. And if anybody is interested in getting involved in the upcoming WREN project looking at Head Injuries in Neonates on the Postnatal Ward please get in touch at [email protected]!

0 Comments

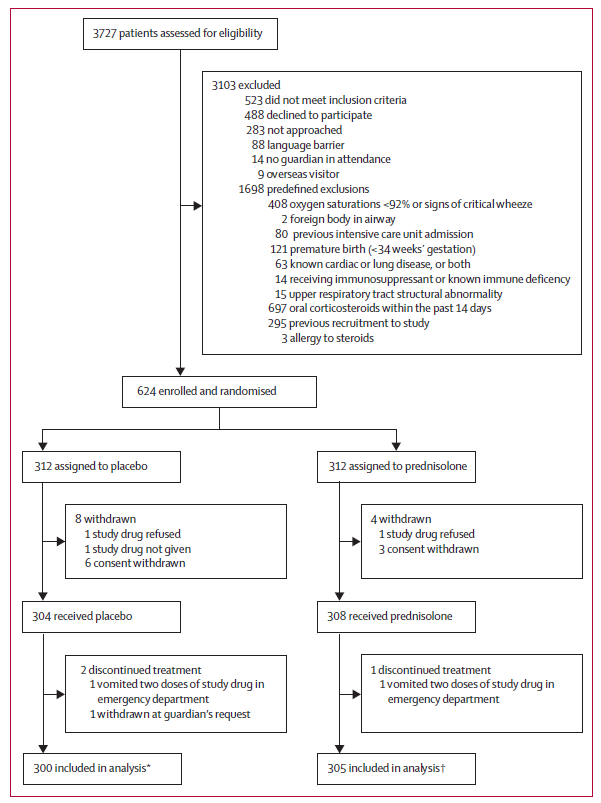

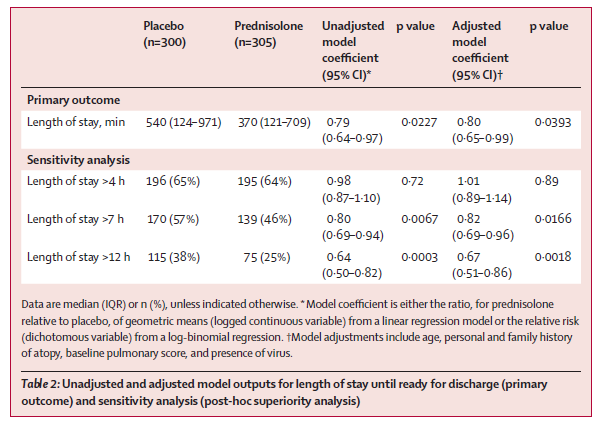

Rebecca Broomfield With a busy family and work life my pile of “must read” journal articles grows larger and larger month by month. However, when the article below popped up on my twitter feed during January it was so relevant to what I do currently every shift and there are a significant number of differing views and options it immediately jumped to the top of the list! (And I actually read it!) The topic of whether to give steroids or not to give steroid when a preschool child presents with wheeze is one which causes huge debate and which I frequently question my own management on. A previous paper published by Panickar et al in 2009 changed our practise and guidelines, despite having questions about the applicability of the study. However, the paper outlined below suggests that we still have more to think about.  Oral Prednisolone in preschool children with virus-associated wheeze: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. S.J. Foster, M N Cooper, S Oosterhof, M L Borland The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2018 January 17 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30008-0 Study Aim To assess the efficacy of oral prednisolone in children presenting to a paediatric emergency department with suspected viral wheeze. The study was originally a non-inferiority trial designed to test the hypothesis that a placebo is non-inferior to prednisolone, the authors added in a superiority analysis, testing the hypothesis that prednisolone was superior to placebo. The secondary hypothesis was added after the data had been collected but prior to data analysis. Participants Eligible patients were between 2- 6 years of age who presented to the paediatric emergency department in Princess Margaret Hospital, Perth, Australia and had a clinical diagnosis of wheeze combined with symptoms of a viral upper respiratory tract infection. Patients were excluded with: Oxygen saturations <92% in air, a silent chest, shock or sepsis, previous PICU admission with wheeze, prematurity, other cardio-respiratory disease, likely alternative diagnosis for wheeze, steroid treatment within the preceding 14 days, allergy to prednisolone or previous study recruitment. The eligibility criteria were suitable for the objective and looked at a population of children who regularly present with viral wheeze. The authors have excluded the bronchiolitis age group of children by excluding children under 2. This is important because they respond to different management. Design There were 3727 patients assessed for eligibility. After exclusions 312 were put into the placebo arm and 312 into the prednisolone arm. Following withdrawals 300 were included for analysis in the placebo group and 305 for the prednisolone group. Prior to data collection the authors calculated a sample size in order to ensure significant results. This was calculated on the original aim of non-inferiority. The study was a randomised double blind trial. Once eligible the participants were randomly assigned on a 1:1 basis to receive either 1mg/kg once daily of prednisolone or placebo. The placebo was formulated by the hospital and matched the prednisolone for volume, concentration, colour, smell and taste. The drugs were in matching bottles and randomisation was appropriate. The blinding for parents, patients, doctors, the research team and biostatician was kept until the statistical analysis was completed. The initial drug dose was administered by a nurse but for the following 2 days were given by the parents at home. The severity of the wheeze was assessed prior to treatment using a calculated pulmonary score. The family completed a questionnaire about home management and previous symptoms and a viral swab was taken from each participant. Each patient was managed with bronchodilators in line with the hospital policy. If the patient who was included in the study was admitted to the ward, and the admitting doctor felt that the patient should receive steroids, then these were given. 23 patients in the placebo group were given steroids in these circumstances. These patients were included in the intention to treat arm and the continuation of the study drug, alongside the prescribed prednisolone was at the discretion of the patient and their parents. They were included in the analysis and if anything would have made it more difficult to demonstrate a statistical significance between the groups. A pulmonary symptom scoring system was used for each patient to group wheeze severities together for analysis which enabled comparisons between groups, and to assess whether initial symptom severity was responsible for patient outcomes. All staff were competent in its use, however, this has score not been validated in children less than 5 years old. Outcomes This paper only comments on some of the data collected during the trial, the remaining data on long term outcomes will be presented in further manuscripts. The initial dual primary outcomes were length of stay in the emergency department and the total length of stay within the hospital. Secondary outcomes (within the first 7 days after hospital discharge) included: reattendance, readmission, salbutamol usage and residual symptoms after discharge. During the data collection it was felt the initial primary outcome; length of stay within the emergency department, was not reflective of the clinical condition as it was dependent on many non clinical factors. The study therefore only looked at an outcome of total length of stay in hospital until the participant was fit for discharge. This change was clearly outlined by the authors and appropriate for the aim of the study. Analysis The study groups were well balanced and the authors found no significant differences between groups in: baseline demographics; pulmonary score at presentation; personal or family history of atopy; use of salbutamol before attendance to the department. Categorical variables were analysed using a χ2 test or fishers exact test and continuous variables were compared using Students t test. Therefore a previously identified risk factor of personal or family history of atopy did not affect the outcomes in this study. Linear regression is the main analysis used to see if outcomes differ for the 2 groups. The authors conclude:

Subgroup analyses:

Secondary outcomes assessed were around representation post discharge. 26 patients re-attended (15 from prednisolone arm and 13 from the placebo arm). 3 patients from the prednisolone group and 2 patients from the placebo group were then prescribed steroids. One patient, from the prednisolone group needed admission to PICU. The statistical analysis of the reattenders (secondary outcomes) was not made clear within the article. Discussion The authors discuss their results in regards to the Panickar 2009 paper; they postulate that the study design could go some way to explaining the different outcome. The authors outline that they have tried to address some of the identified limitations found in the 2009 paper. These include the exclusion of children under 2 years old, thus reducing the likelihood for inclusion of patients with bronchiolitis. They urge some caution within their subgroup analysis conclusions as the sample size was smaller than the sample size used for calculating the general conclusion, also the patients were not randomly allocated to the arms based on the severity of symptoms or the use of salbutamol prior to attendance. This presentation is something we see daily in the emergency department and children’s assessment unit. It is an area for which I don’t feel that we have fully understood all the physiology behind the presentations. There are most likely many phenotypes of childhood wheeze. More research is definitely needed in order to assess the need for steroids and how to select the patients who would benefit from them. I look forward to reading further papers on the more long term conclusions of this trial. I think that I will still continue to judge the need for steroids on a patient by patient basis. Questioning with each patient whether they should or should not receive steroids. (And we’ve not even touched on Dexamethasone vs. Prednisolone!) It would be great to hear your views on this topic, I encourage you to comment on the blog or tweet me. (@RCBroomfield) Have a lovely February Rebecca The previous paper referenced can be found at: Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, Kenia P, Stephenson T, Smyth A, Grigg J. Oral Prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus induced wheezing, New England Journal of Medicine. 2009 Jan 22;360(4);329-38 By Katherine Burke (Neonatal GRID Trainee, Wales Deanery; Welsh Clinical Academic Trainee) [email protected] Twitter: @DrKNeely Following on from the presentation at the WREN Autumn Study Day 2017, here's the 30-second guide to the best resources to use to get involved in research and get funding! Being ‘Involved’ in Research: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/improving-child-health/research-and-surveillance/research-opportunities/get-involved-research/get-in http://www.peruki.org/ Lists projects which are ongoing. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/bpsu/bursary Fantastic opportunity to design and carry out a project in partnership with the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit. Potential Sources of Funding for PhD For projects which are already ’set up’ i.e. designed and funded, see www.findaphd.com https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/research_funding_opportunities The RCPCH curate a list of funding opportunities – you need to be logged in with your college account but it is really comprehensive, and great for ‘specifics’ i.e. funding streams and opportunities related to particular conditions. https://wellcome.ac.uk/funding Wellcome provide grants for people undertaking particular projects. If you have an idea and a supervisor in mind, there are multiple streams under which you can apply i.e. Biomedical Sciences, Medical Humanities (for society/ethics projects) or International Development. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/funding/how-we-fund-research/ Similar to Wellcome. https://www.sparks.org.uk/ https://www.action.org.uk/our-research/apply-research-grant/apply-project-grant Dedicated to funding Paediatric Research. Again, need a project idea and a sponsor and supervisor in place. Disease specific opportunities….. (NOT comprehensive, just some examples!) https://www.kidneyresearchuk.org/research/paediatric-research-applications http://christopherssmile.org.uk/research/ https://www.childrenwithcancer.org.uk/research/for-researchers/funding-opportunities/ https://www.epilepsyresearch.org.uk/research-scientists/apply-for-funding/ Writing a ‘Research Proposal’

When developing a project idea, a good place to start is by carrying out a ‘literature review’ outlining the current status of knowledge for a particular area or field. If you contact the library at UHW, there is regular training available on ‘how to do….’ literature searches, among other useful things. https://www.nbt.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/How_to_write_a_research_proposal.pdf |

Editors

Dr Annabel Greenwood Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed