|

Dr Tom Cromarty Editor Interests: Paediatric Emergency Medicine, Medical Engagement and Leadership, Simulation, Quality Improvement, Research Twitter: @Tomcromarty |

Welsh Research and Education Network

WREN BlogHot topics in research and medical education, in Wales and beyond

Dr Celyn Kenny Editor Interests: Neonates, Neurodevelopment, Sepsis, Media and Broadcasting Twitter: @Celynkenny |

|

Guest blog post by Dr Kimberley Hallam I’m an ST2 in paediatrics and unfortunately did not have the chance to attend the RCPCH conference last year. So, this year I was very excited when I realised, not only would I be able to attend for all 3 days, but it was also in Glasgow…a city which I love and where my twin sister lives. Getting up to Glasgow itself was challenging! I travelled up after work on the Wirral on Monday night. Soon after leaving, there was an announcement that there were trespassers on the line. Unfortunately, this meant I didn’t arrive at Glasgow Central Station until 00:45! Luckily, I was staying with my sister so didn’t have the hassle of a late night check in. DAY ONE Day one of the conference was entitled the ‘Science and Research’ day. Because of my late arrival to Glasgow, I didn’t attend the 8am ‘Personal Practice Sessions’, but started at 9am with a welcome from the (now ex-) President of the RCPCH, Neena Modi. During the course of the conference, she relinquished her presidential title to Russell Viner. She gave an eloquent opening talk which was followed by a presentation by the RCPCH & Us Network. This is a group of young people who work with the RCPCH to ensure that young people’s views are listened to in all matters within the RCPCH organisation. They spoke incredibly well and are clearly a group of passionate, intelligent young people who are forward thinking, keen to bring about change and ensure their voices are heard. Another highlight from the morning included a talk by Prof. David Archard regarding children and parental rights. He took examples from recent high profile cases and presented ethical considerations regarding parental rights. He focussed on a public slogan taken from the Charlie Gard Case: ‘My Child, My Choice.’ After a fascinating discussion, he concluded that ‘disagreements [between medical staff and parents] will continue and [will] probably proliferate. Parents’ feelings and views count but they are not decisive.’ He closed the session with the remark that ‘we live in a time of post-truth and populism.’ Next came an interesting presentation from Dr Cherry Alviani and was entitled ‘Sleep for your own health: A Pan-UK Survey on Paediatricians Experience of Sleep Around Shift Work.’ She talked about a survey she completed which showed a lot of trainees do not have training on how to manage sleep around night shifts and that many hospitals do not provide somewhere for trainees to sleep on night shift and/or do not support them doing so. Given lack of sleep affects judgement and clinical performance, these are important issues to address. As an aside, the BMJ have recently published a brilliant article which gives general advice on how to survive night shifts and which I have personally found quite useful: http://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.j5637.full After the plenary session, I attended a workshop entitled ‘Press, Politics and Paediatricians; Campaigning for Child Health Across the UK.’ This was an interactive workshop and even had some role play where members of the audience acted as news reporters and grilled (a pretend) Jeremy Corbyn and Jeremy Hunt. Suffice to say, this became a little heated! Overall, the session introduced the idea that it is our duty as paediatricians to be advocates for child health. This may include being politically active (e.g lobbying government) or may involve speaking out on behalf of paediatricians/children in the press. The RCPCH have opportunities for members to become involved in such work on their Press and Parliamentary Panels (they include free training). I’ve put this link here so you can have a wee look if you’re interested: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/news/membership-benefit-month-media-and-parliamentary-training The last session of the day I went to was run by the British Association of Paediatricians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) and covered ‘Hot topics in paediatric subspecialties.’ They had a number of insightful and interesting talks including ‘When do you need a gut specialist?’, ‘Chronic cough: when is it a cause for concern?’ and ‘Changing landscapes in paediatric epilepsy.’ They also had talks from Neena Modi and Russell Viner (who got a bit of a kind-hearted grilling from the audience after his talk ‘Paediatric services: fit for the future’. I chose not to go to the meal out on the first night. Instead, I went to a fabulous place in Glasgow called Stravaigin with my sister and a Mersey trainee. It comes highly recommended! DAY 2 Day two of the conference was the ‘Global Child Health Day’ and, I have to admit, the day I was most looking forward to. It did not disappoint. The day kicked off at 8am with a session on how to include global health in your career which was delivered by a diverse group of trainees who all had experiences of working in global health during their training years. They introduced the variety of ways a trainee can take part in global health work. These include clinical work, teaching, quality improvement projects, research and public health. The session covered considerations such as the stage of training you should aim to do such work, what support you might receive and where you can do the work. They also talked about the courses you can go on to help prepare. For example, ETAT, CHILS, GIC and the Diploma of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. I left this session feeling very inspired and excited about my potential future opportunities. Next up was the plenary with the first person to speak Prof Anthony Costello (Director of the Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, World Health Organisation). He gave a keynote speech on ‘Global governance for child health and sustainable development.’ As his title suggests, he came across as a very inspirational person. He questioned ‘is everything getting better?’ He stated that, globally, child mortality is improving rapidly and maternal mortality is improving but not to the same extent. As currently projected, low income countries will not catch up with higher income countries for a great number of years. Globally, we are still falling short in harder to reach areas and there are still basic health needs which are not being met. For example, lack of access to clean water and sanitation. Five key problems which act as a barrier to improving child health are as follows: 1. Fragmentation of global child health strategies undermines programming and limits impact 2. Child health goals will not be met without adequate funding and delivery to marginalised populations 3. Evidence is not systematically generated and integrated into policy and programs 4. Strategies are insufficiently tailored to country context, and tools need improved end-user design 5. Lack of accountability, clear targets and strong monitoring He then went on to describe five key areas for WHO and UNICEF to address. The next talk was regarding child refugee health and is something I have been interested in for a long time and passionate about since attending the Royal Society of Medicine’s study day ‘Child Refugee Health: Everyone’s Responsibility.’ Dr Marylyn Emedo presented data on ‘Adverse experiences of Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking children (UASC) and the impact on their emotional wellbeing and mental health needs.’ As a bit of background, there were 3290 unaccompanied asylum seeking children in the UK in 2016. Children from Afghanistan, Albania and Eritrea formed 48% of all UASC in 2016. Her study was a retrospective review of records of all UASC referred to a clinic run by a local authority in London between 1st January to 31st August, 2016. The study focussed on adverse experiences the children went through on their journey to the UK. It found that 51% of children experienced trauma on route to the UK including detention, beating, torture and sexual assault. All the children in the study were screened for mental health needs. Of these, 75% reported at least one symptom suggestive of PTSD, anxiety or depression and 43% accepted a referral to CAMHS. Her recommendations were for timely review in line with statutory guidelines and initiation of early support by mental health services. Next, the workshop I chose to attend was ‘What should RCPCH’s global health priorities be?’ This started with a talk outlining some stark facts: 98 of every 100 children who die <5 years, die in developing countries, mainly from avoidable/treatable causes. There has also been a shift of mortality from communicable to non-communicable diseases. There followed a discussion surround how to address these issues as we work towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDPs) set by the UN (http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/). There was participation from the audience and good engagement from the RCPCH. I was particularly happy to hear that the RCPCH are launching a global health professional development framework to run alongside paediatric training in order to engage trainees in global health work. I continued the global health theme by attending the International Child Health Group’s afternoon session. This took part in the main Clyde auditorium and was mainly delivered by people who had conducted projects related to international health. The first talk was delivered by Dr Jonson and was entitled ‘The validation of transcutaneous bilirubin as a method to monitor newborn jaundice in a low income country.’ She had recognised there were significant problems with babies developing kernicterus as a result of untreated jaundice in Haiti. Despite having a reasonably small data set, her study suggested that transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring was a safe way of measuring bilirubin in a low income country. The unit she was working on had a lower incidence of kernicterus following the trial. However, she suggested a larger data set would be required to fully validate her findings. Amongst the remainder of the afternoon talks, the one which stood out for me was given by Dr Christopher Hands and entitled ‘Delivering nurse-led emergency paediatric care in Sierra Leonean Hospitals: The effect on quality of care and mortality.’ This nurse-led care involved the introduction of triage systems, stream-lining the patient journey at the point of care and training nurses in ETAT. These basic interventions had resulted in a very impressive reduction in mortality. Anecdotally, nurses now recognised they had the skills to save the lives of individuals presenting with symptoms they previously thought they could do nothing for. For example, hypoglycaemia and seizures. Other talks included ‘Neonatal outcomes from FGM/cutting in the Gambia; results from a multicentre prospective study’, ‘The use of satellite clinics in W Uganda to remove barriers to seeking care’ and ‘Identification of the health burden for street children and service provision available in Kismu, Kenya, through Focus Group Discussions.’ At the end of the second day, I was exhausted. However, thanks to this day and the enthusiastic way in which the RCPCH approach global health, I now have a renewed determination to pursue a career in this area. DAY 3 Day three was entitled the ‘Health Services for Children day.’ The plenary in the auditorium started with a keynote speech from Prof. Jason Leitch, the National Clinical Director from Scottish Government. He was a very entertaining and enthusiastic speaker and it really was a pleasure to listen to him in his home city of Glasgow. He talked about the state of child health inequality in Scotland. He described how children living in Glasgow within a few miles of each other have a very different life expectancy (a phenomenon which is termed the ‘Glasgow Effect’). He then went on to talk about various local programmes which had been set up. For example, a programme in which fathers in prison are given intensive parenting classes and have their children visit the prison regularly. This even involved the inmates performing a play of the Gruffalo for the children and has the benefit of decreasing their chance of reoffending. There have also been programmes which involve intensive health visitor input. He ended with the following picture. After the plenary and a short refreshment break, it was time for the final workshop session. As I seemed to be developing a political interest as the conference went on, I decided to attend the session ‘Child Health Policy Development: Why, What and How?’ This started with a presentation regarding the RCPCH health policy strategic direction for 2018. This states that the RCPCH wants to achieve the following:

1. To prioritise the health needs of infants, children and young people 2. To prevent ill health and promote health and wellbeing 3. To ensure continuous improvement in the quality of healthcare services 4. To reduce child health inequalities They plan to achieve these aims in the following way: 1. Developing robust, evidence-based policy 2. Prioritisation and horizon scanning 3. Understanding the environment we work in 4. Influencing the right decision makers, at the right time 5. Having a tailored approach so the right messages reach decision makers across the UK After the presentation, there was a discussion with audience participation and engagement from the new president. We discussed why and how the RCPCH develops policy, its impact and the role of paediatricians in influencing decision makers. We concluded that, as paediatricians, we have a duty to advocate on behalf of children and young people and part of that involves lobbying to push child health up the political agenda. Following the workshop and lunch, I decided to start the first part of the afternoon with the ‘Children’s Ethics and Law Special Interest Group’ (CHELSIG). After an introduction to CHELSIG, there was a presentation ‘Children’s rights, UK healthcare and Brexit: Could things get worse for young people?’ This session discussed the UN rights of the child, including Article 16 (the views of the child), Article 24 (health and health services) and Article 16 (young people have the right to a private life). According to a study completed by the NIHR, 57% of children felt they were not involved or only involved a little in their care. This session encouraged paediatricians to involve children in decisions about their care and consider facilitating groups where children and young people can provide input into the running of paediatric services. The next session was called ‘Moral distress, trauma and burnout in staff in relation to changes in PICU outcomes, challenging cases and media involvement in disagreements about end of life care.’ This session was led by Gillian Coleville who had studied the impact of the above in Great Ormond Street staff following the Charlie Gard case. The staff highlighted their main sources of distress are being accused of not caring, public condemnation without the right to reply, fears for their own safety, witnessing a child’s suffering, protracted legal proceedings, impact on other families and constant changes to care plan. 15% of staff had features of clinically significant post-traumatic stress syndrome. I was quite surprised at how high this was and also found it distressing to hear how the case had impacted upon their private lives. The final session I went to on day 3 was one run by the Association of Paediatric Emergency Medicine. This was an afternoon focussing on the Manchester Arena bombing on 22nd May, 2017. We heard from Allan Courdwell, Head of Group Emergency Planning with the Northern Care Alliance who talked us through what happened on the day and how the trust managed the major incident. This was followed by an insightful talk by Fiona Murphy MBE, Associate Director of Nursing who covered the bereavement response after the bombing. She gave a moving description of how the bereavement officers supported those who suffered the death of a loved one. Her commitment to providing dignified support to the families was exceptional. She described various ways in which she co-ordinated and delivered the bereavement support. This included putting families up in a hotel together, having 24-hour access to a bereavement officer and finding out information regarding the victims so they could, for example, play their favourite music when families were viewing their bodies. She also arranged for the families to visit the arena (when safe to do so) where they had lit a candle where each of the victims was found so the families could further understand and come to terms with what had happened. This talk moved me and many others to tears and I was so overwhelmed by the dedication she and her team showed to support the families in the aftermath of the bombings. So, that concluded my first attendance at an RCPCH conference and I really enjoyed the experience. It was great to see how proactive the college came across in providing advocacy for children and addressing global child health. It was also fabulous to catch up with old friends and be inspired by projects which other paediatric trainees are undertaking throughout the country. I’ll definitely aim to go again next year!

0 Comments

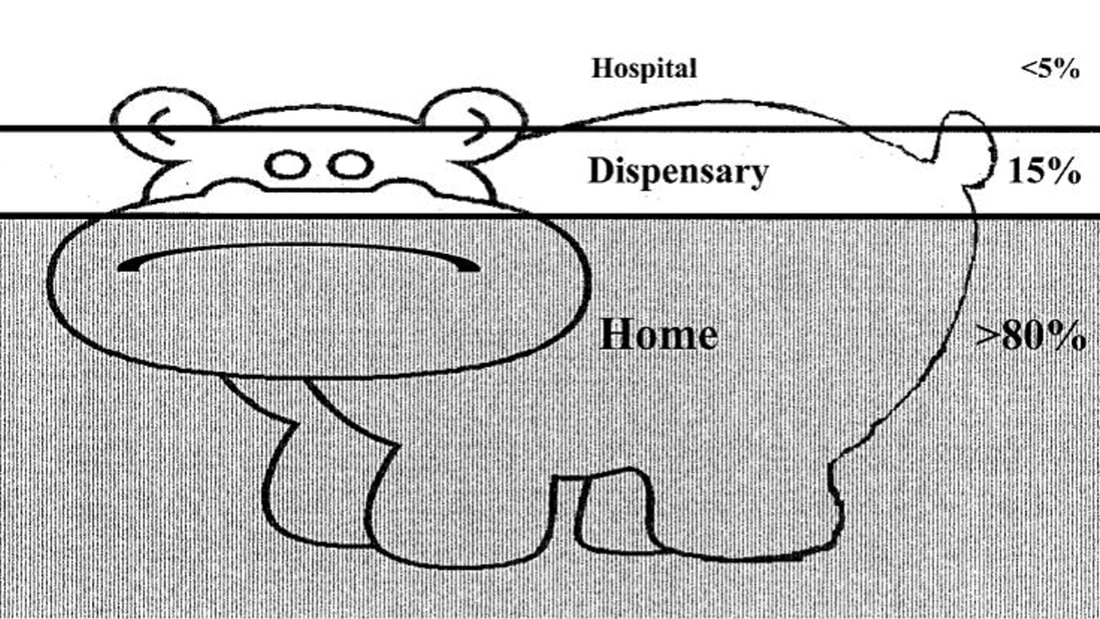

Guest Post by Dr Emily Clark The Sustainable Development Goals, launched in 2015, are ambitious. For example: "By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births” This is a tough challenge we have set ourselves. Current global neonatal mortality (NMR) stands at 19/1000 live births, with under-5 mortality (U5M) at 41/1000 live births. In Madagascar, the NMR is 19/1000 live births, and the U5M 46/1000 live births (1). Note that these figures are all averages, which hides variation between regions, between rich and poor, between the educated and the illiterate (Hans Rosling has an excellent talk on this). I worked in a remote coastal region of southwest Madagascar, where there are no local data available for neonatal or child mortality as many births, and deaths, are not registered. I imagine that the statistics here would be worse than the average as communities are subject to the inverse care law: the paradox that those with the greatest need for health care have the least access. However, in terms of mortality rates, we have come a long way already. At the start of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 1990, the global NMR was 37/1000 live births (40/1000 in Madagascar), and the U5M was 93/1000 live births (160/1000 in Madagascar) (1). The Millennium Development Goals report states: “The dramatic decline in preventable child deaths over the past quarter of a century is one of the most significant achievements in human history” So what works, and what do we need to do? We know that most childhood illnesses are managed at home. This is memorably described in the case of malaria as the “ears of the hippo” – where only the minority of children are seen in a health facility. ‘‘The Ears of the Hippopotamus’’ where malaria patients are managed . . . and die. (2) How do we get children from home to the hospital? And how do we do so within a timely manner? The three delays model was devised in 1994 by Thaddeus and Maine (3). It states that the delay in a sick person receiving appropriate medical care can be broken down as follows: 1. The delay in recognition that medical help is required 2. The delay in arriving at a location where appropriate medical help can be given 3. The delay in receiving appropriate help at this location Rather than making the sick travel to the health centre, bringing health workers into the communities has demonstrated a reduction in childhood mortality. This initiative, known as Integrated Case Community Management (ICCM), targets the top causes of childhood deaths: diarrhoea, malaria, and pneumonia. If implemented globally, early treatment in the community of pneumonia in under-fives could reduce mortality by more than two-thirds. Similarly, community-based treatment of malaria could halve malaria-related mortality. Three-quarters of deaths from diarrhoea could be prevented by administration of oral rehydration solution (4). ICCM also promotes identification and treatment of malnutrition, which is observed in one-third to one-half of childhood deaths. I volunteered with Blue Ventures, a marine conservation NGO, working in remote coastal southwest Madagascar. I worked with their community health team, Safidy, which means “choice” in Malagasy. Here, it is all too easy to understand how receiving timely and appropriate medical intervention was a challenge. Health literacy was poor, transport infrastructure was sparse (relying on zebu carts, fishing pirogues, and ad hoc cars and lorries). The roads were sandy tracks, and driving to the city takes 7 hours to cover the 200km on a good day – and that was in a 4x4. Sadly, this is unaffordable to most. Poverty underlies life here. There is no money available for medicines, transport; many can simply not afford not to work for a day. As part of the Safidy programme, each village in the Blue Ventures service area has one agent communautaire (AC). These ACs, already respected women within their communities, were invited by the ICCM programme to an intensive eight-day residential training course. The training was centred around the use of a fiche, a paper-based form containing a series of questions which guide the ACs through key symptoms to aid diagnosis, and the “danger signs” of serious illness. These danger signs should prompt immediate treatment, as specified by the fiche, and referral to a health centre. The fiche guides ACs in providing safety net advice and follow up arrangements. The ACs also educate communities regarding public health measures, such as promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, and immunisations. ACs are provided with key items of equipment, such as rapid diagnostic tests for malaria, a measuring strip for mid-upper arm circumference for assessment of malnutrition, and a one-minute timer for measuring respiratory rate. Essential medicines are also provided, including oral rehydration solution and zinc, antibiotics for pneumonia, and anti-malarials. When a child falls ill, it is easy for the family to ask the AC within their own village for advice. The AC is able to assess and triage the child, and decide, using the fiche, what treatment is required. For example, a child presenting with a cough may well have pneumonia; the AC should then check for fever, and measure the respiratory rate. If the respiratory rate is raised, this should prompt antibiotic treatment and referral to a health centre. If there are no danger signs present, then the AC can provide a course of antibiotics and appropriate follow up advice. All the ACs are literate, however, they have had very limited education at school. Yet, these women perform the same job that we do, as a multi-disciplinary team, in the Children’s Assessment Unit. They are simply phenomenal. It is a lot to learn, and so, together with a local ICCM trainer, the Safidy team arranged for two study days for the newly-trained ACs. The focus was on role play rather than theory. Many of the ACs had brought their children along to the training and so they made for excellent “patients”, and so we witnessed some Oscar-worthy performances! Each AC received feedback on their performance: what went well, what could be improved next time. The ACs will now spend time working under direct supervision from nurses and midwives at local health facilities, before being approved to work independently within their communities. We hope that the success of ICCM in other countries can be replicated in this little corner of Madagascar. One AC measures a young actor’s respiratory rate using a specially-designed timer A trainer demonstrates assessment for pedal oedema; a danger sign that should prompt referral to a health centre Further reading For more reading on the Sustainable Development Goals: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ The WHO have produced a report on the evidence for ICCM, available here: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/iccm_service_access/en/ To see data being brought to life, I would advise watching Hans Rosling – starting here: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen ICCM complements the WHO programme Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) which aims to improve the quality of care available to patients at health facilities. A recent Multi-Country Evaluation has demonstrated that quality of care is improved, resulting in a reduced childhood mortality. It has demonstrated cost-effectiveness, as earlier and correct treatment saves money. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/child/imci/en/ For more information regarding Blue Ventures’ community health programme, Safidy: https://blueventures.org/conservation/community-health/ References:

(1) All data from the World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/ Accessed 20.03.2018 (2) The Intolerable Burden of Malaria: A New Look at the Numbers: Supplement to Volume 64(1) of the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Breman JG, Egan A, Keusch GT, editors. Northbrook (IL): American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2001 Jan. (3) Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Apr;38(8):1091–110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 pmid: 8042057 (4) WHO/UNICEF JOINT STATEMENT Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM). United Nations Children’s Fund. 2012 Guest blog by Dr Jemma Wright I was delighted to attend the first day of the RCPCH annual conference this year and here is a brief summary of my day. The day started early with a personal practice session about the new PROGRESS curriculum. Hopefully you are all aware of this new curriculum as it is going to be introduced this August. The session was an introduction to the new curriculum and it does seem like the college is trying to make it easier to engage with the new, much shorter curriculum. There is lots of information available on www.rcpch.ac.uk/progress including details of the mandatory 'key capabilities' we need to achieve and 'illustrations'/examples of how to evidence this on Kaizen. The main tip was to engage with this curriculum early as you can start producing evidence on your eportfolio now so it is already there to link to the new curriculum when it becomes live on 1st August 2018. The overall theme of the conference was ‘Children First – Ethics, Morality and Advocacy in Childhood’ and the main plenary had a strong theme on ethics.

The first keynote speech was about “Putting the Child First” and was an extremely topical philosophical exploration of the interaction between best interests and parental rights. There has been some significant media attention in the last year on multiple cases of disagreement between the medical teams and the parents. He alluded to these cases including the common protest of ‘my child, my choice’, and put a spin on this statement by highlighting that a parent does not necessary have the right to choose anything for their child – his example being that parents have the right to choose what to feed their child but they cannot choose to feed them poison. Overall it was an interesting discussion concluding that the child must always come first. This was followed by three project presentations: The first was on the impact of austerity on families with disabled children across Europe. The conclusion of the project survey was that cuts since 2008 have resulted in worsening quality and access of services to disabled children with a significant negative impact on families in the UK, especially those in severe poverty. The second was about delays in seeking legal judgements in cases of withdrawal of care, collecting data of 15 cases across the England over the last 5 years. They recommended considering alternative methods to avoid these delays such as mediation/dispute resolution, which have high success rates in avoiding litigation, and tend to have higher satisfaction rates. The last project was about a UK survey on paediatricians experience of sleep education. It was found that around 75% of paediatric trainees have not received any teaching on sleep during their training. Interestingly they recommended that we should all be taking a 15 min nap during our night shifts to reduce fatigue and that this should be supported by our workplaces. For more information, they have recently published articles in ADC and BMJ to promote more awareness about how to approach sleep during shift work. The plenary concluded with Professor Neena Modi talking about “Children in the 21st century’ focussing on the historical progression of a child’s role in society from possession, to protection, to partnership. She also talked about the increasing importance of non-communicable diseases in children especially childhood obesity and the interaction between child health and adult health. There is a whole section about these issues in the State of Child Health section on the RCPCH website. Next up, I chose to go to a workshop about navigating academic training pathways. As a non-academic trainee, it was interesting to hear that the college is keen to support paediatricians interested in developing an academic element to their job. I found out about a research funding opportunities database on the RCPCH website (https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/research_funding_opportunities) and the new academic toolkit (http://apatoolkit.eastface.co.uk). After lunch, I headed to the BPAIIG speciality group session. We had a presentation from an epidemiologist at PHE taking about paediatric antimicrobial resistance followed by a talk by a paediatric ID consultant about balancing antimicrobial stewardship since the new NICE sepsis guidelines. The key learning point when prescribing antibiotics was to be mindful of antibiotic resistance and always ‘Start Smart then Focus‘. There was a good representation from Wales in this session. I was asked to present my project about the epidemiology/microbiology of candidaemia over the last 15 years at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital followed by an excellent presentation by a Cardiff medical student looking at the risk of laceration when using an adrenaline auto-injector. There were also two further presentations about the impact of PCV on pneumococcal meningitis rates and two cases of INF a/b receptor 2 deficiency associated with immunodeficiency. Finally there were two further talks by paediatric ID consultants about the use of biomarkers to guide length of antibiotic course and the novel use of old antibiotics or new antibiotic combinations to treat multi-resistant bacteria. Excitingly there is a new national trial entitled BATCH (biomarker guided duration of antibiotic treatment in children hospitalised with confirmed or suspected bacterial infection), which is being coordinated by the Centre for Trials Research in Cardiff and may guide further developments in this area. Overall I had an excellent thought provoking day and enjoyed the excuse to visit Glasgow, my old FY2 home. |

Editors

Dr Annabel Greenwood Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed