|

Dr Tom Cromarty Editor Interests: Paediatric Emergency Medicine, Medical Engagement and Leadership, Simulation, Quality Improvement, Research Twitter: @Tomcromarty |

Welsh Research and Education Network

WREN BlogHot topics in research and medical education, in Wales and beyond

Dr Celyn Kenny Editor Interests: Neonates, Neurodevelopment, Sepsis, Media and Broadcasting Twitter: @Celynkenny |

|

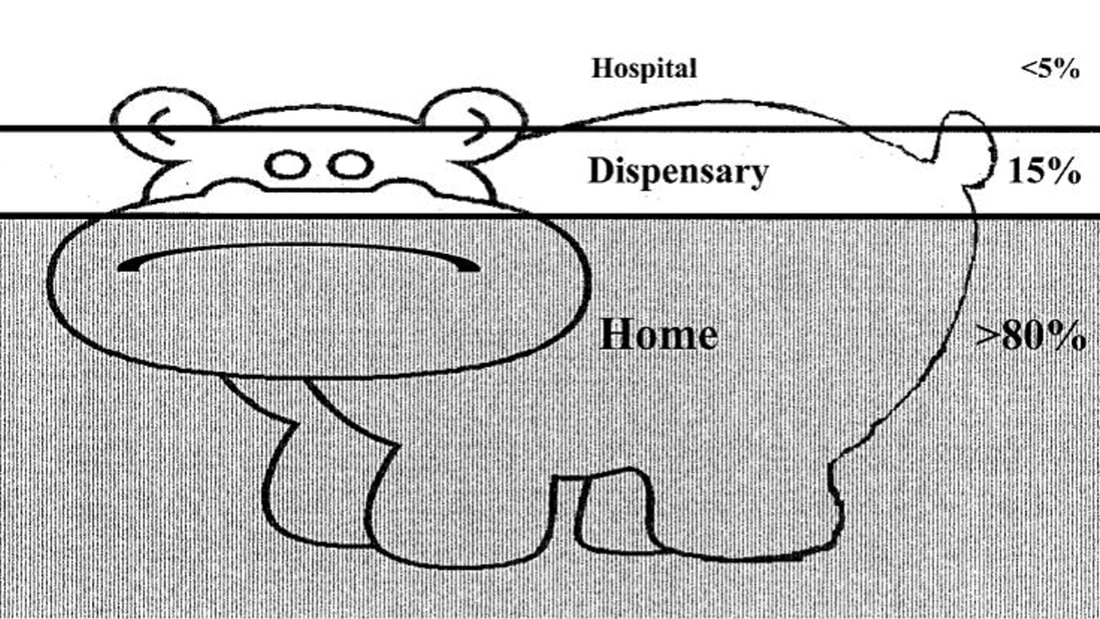

Guest Post by Dr Emily Clark The Sustainable Development Goals, launched in 2015, are ambitious. For example: "By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births” This is a tough challenge we have set ourselves. Current global neonatal mortality (NMR) stands at 19/1000 live births, with under-5 mortality (U5M) at 41/1000 live births. In Madagascar, the NMR is 19/1000 live births, and the U5M 46/1000 live births (1). Note that these figures are all averages, which hides variation between regions, between rich and poor, between the educated and the illiterate (Hans Rosling has an excellent talk on this). I worked in a remote coastal region of southwest Madagascar, where there are no local data available for neonatal or child mortality as many births, and deaths, are not registered. I imagine that the statistics here would be worse than the average as communities are subject to the inverse care law: the paradox that those with the greatest need for health care have the least access. However, in terms of mortality rates, we have come a long way already. At the start of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 1990, the global NMR was 37/1000 live births (40/1000 in Madagascar), and the U5M was 93/1000 live births (160/1000 in Madagascar) (1). The Millennium Development Goals report states: “The dramatic decline in preventable child deaths over the past quarter of a century is one of the most significant achievements in human history” So what works, and what do we need to do? We know that most childhood illnesses are managed at home. This is memorably described in the case of malaria as the “ears of the hippo” – where only the minority of children are seen in a health facility. ‘‘The Ears of the Hippopotamus’’ where malaria patients are managed . . . and die. (2) How do we get children from home to the hospital? And how do we do so within a timely manner? The three delays model was devised in 1994 by Thaddeus and Maine (3). It states that the delay in a sick person receiving appropriate medical care can be broken down as follows: 1. The delay in recognition that medical help is required 2. The delay in arriving at a location where appropriate medical help can be given 3. The delay in receiving appropriate help at this location Rather than making the sick travel to the health centre, bringing health workers into the communities has demonstrated a reduction in childhood mortality. This initiative, known as Integrated Case Community Management (ICCM), targets the top causes of childhood deaths: diarrhoea, malaria, and pneumonia. If implemented globally, early treatment in the community of pneumonia in under-fives could reduce mortality by more than two-thirds. Similarly, community-based treatment of malaria could halve malaria-related mortality. Three-quarters of deaths from diarrhoea could be prevented by administration of oral rehydration solution (4). ICCM also promotes identification and treatment of malnutrition, which is observed in one-third to one-half of childhood deaths. I volunteered with Blue Ventures, a marine conservation NGO, working in remote coastal southwest Madagascar. I worked with their community health team, Safidy, which means “choice” in Malagasy. Here, it is all too easy to understand how receiving timely and appropriate medical intervention was a challenge. Health literacy was poor, transport infrastructure was sparse (relying on zebu carts, fishing pirogues, and ad hoc cars and lorries). The roads were sandy tracks, and driving to the city takes 7 hours to cover the 200km on a good day – and that was in a 4x4. Sadly, this is unaffordable to most. Poverty underlies life here. There is no money available for medicines, transport; many can simply not afford not to work for a day. As part of the Safidy programme, each village in the Blue Ventures service area has one agent communautaire (AC). These ACs, already respected women within their communities, were invited by the ICCM programme to an intensive eight-day residential training course. The training was centred around the use of a fiche, a paper-based form containing a series of questions which guide the ACs through key symptoms to aid diagnosis, and the “danger signs” of serious illness. These danger signs should prompt immediate treatment, as specified by the fiche, and referral to a health centre. The fiche guides ACs in providing safety net advice and follow up arrangements. The ACs also educate communities regarding public health measures, such as promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, and immunisations. ACs are provided with key items of equipment, such as rapid diagnostic tests for malaria, a measuring strip for mid-upper arm circumference for assessment of malnutrition, and a one-minute timer for measuring respiratory rate. Essential medicines are also provided, including oral rehydration solution and zinc, antibiotics for pneumonia, and anti-malarials. When a child falls ill, it is easy for the family to ask the AC within their own village for advice. The AC is able to assess and triage the child, and decide, using the fiche, what treatment is required. For example, a child presenting with a cough may well have pneumonia; the AC should then check for fever, and measure the respiratory rate. If the respiratory rate is raised, this should prompt antibiotic treatment and referral to a health centre. If there are no danger signs present, then the AC can provide a course of antibiotics and appropriate follow up advice. All the ACs are literate, however, they have had very limited education at school. Yet, these women perform the same job that we do, as a multi-disciplinary team, in the Children’s Assessment Unit. They are simply phenomenal. It is a lot to learn, and so, together with a local ICCM trainer, the Safidy team arranged for two study days for the newly-trained ACs. The focus was on role play rather than theory. Many of the ACs had brought their children along to the training and so they made for excellent “patients”, and so we witnessed some Oscar-worthy performances! Each AC received feedback on their performance: what went well, what could be improved next time. The ACs will now spend time working under direct supervision from nurses and midwives at local health facilities, before being approved to work independently within their communities. We hope that the success of ICCM in other countries can be replicated in this little corner of Madagascar. One AC measures a young actor’s respiratory rate using a specially-designed timer A trainer demonstrates assessment for pedal oedema; a danger sign that should prompt referral to a health centre Further reading For more reading on the Sustainable Development Goals: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ The WHO have produced a report on the evidence for ICCM, available here: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/iccm_service_access/en/ To see data being brought to life, I would advise watching Hans Rosling – starting here: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen ICCM complements the WHO programme Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) which aims to improve the quality of care available to patients at health facilities. A recent Multi-Country Evaluation has demonstrated that quality of care is improved, resulting in a reduced childhood mortality. It has demonstrated cost-effectiveness, as earlier and correct treatment saves money. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/child/imci/en/ For more information regarding Blue Ventures’ community health programme, Safidy: https://blueventures.org/conservation/community-health/ References:

(1) All data from the World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/ Accessed 20.03.2018 (2) The Intolerable Burden of Malaria: A New Look at the Numbers: Supplement to Volume 64(1) of the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Breman JG, Egan A, Keusch GT, editors. Northbrook (IL): American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2001 Jan. (3) Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Apr;38(8):1091–110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 pmid: 8042057 (4) WHO/UNICEF JOINT STATEMENT Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM). United Nations Children’s Fund. 2012

0 Comments

|

Editors

Dr Annabel Greenwood Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed