|

Dr Tom Cromarty Editor Interests: Paediatric Emergency Medicine, Medical Engagement and Leadership, Simulation, Quality Improvement, Research Twitter: @Tomcromarty |

Welsh Research and Education Network

WREN BlogHot topics in research and medical education, in Wales and beyond

Dr Celyn Kenny Editor Interests: Neonates, Neurodevelopment, Sepsis, Media and Broadcasting Twitter: @Celynkenny |

|

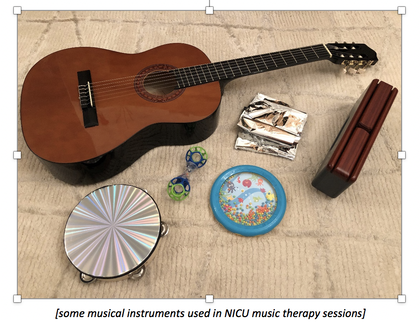

Katie Richards As part of my Master’s (MA) in Music Therapy and my training to become an HCPC-registered qualified Music Therapist (one of the allied health professions), I am fast approaching the end of my final placement, in a regional tertiary-level Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), which consists of an intensive care unit (ITU), a high-dependency unit (HDU), a low-dependency unit (LDU) and a nursery. Part of the requirements for our final placement, which forms most of our Advanced Professional Practice module, was that we had to set up a new music therapy service somewhere which had never had it before (one day per week for around 24 weeks). We could choose any client group or setting, and I was drawn to working with neonates ever since reading an article (scroll to see some reading recommendations!)by chance during the first year of this three-year part-time MA course. I was absolutely thrilled when the Senior Nurse emailed me back within minutes to say they’d love to have me on board! I did lots of preliminary reading around music therapy in the NICU and observed a qualified music therapist working in a different regional NICU prior to commencing my placement, so I had a pretty good idea of what to expect. As with all our placements, this involved six weeks’ observations at the start, before commencing our own clinical work. Our placements are very varied, with my first-year placement having been in a Special Educational Needs (SEN) school working with a child with autism and my second-year placement in a private psychiatric hospital working with in-patient adults with acute mental health issues (and some with complex mental health issues, e.g. chronic schizophrenia and dementia co-morbidly). This sets us up for our future work, where the client groups could be incredibly varied (from pre-birth to end of life, and everything in between). The thing about music therapy is that you usually need a wide variety of musical instruments for different circumstances. Because we often work ‘in the moment’, you just don’t know when you may need something in particular, so it’s better to have it with you than not to. Because of this, I start my day by loading myself up like a Buckaroo – one more stringed instrument and my arm might fall off! Neonatal music therapy sessions can look quite different depending on the patient you’re working with and are adjusted to what that particular baby/parent needs at that moment in time, keeping in line with their broader clinical goals. For example, when working with a term baby who was quite aware of their surroundings and in a quiet-alert state, I used musical instruments with more of a sensory impact to encourage visual tracking (e.g. the shiny, reflective tambourine, the colourful rattle or the colourful wave drum – see photo). Of course, these instruments all work on auditory stimulation, but with the added benefit of visual stimulation and tactile stimulation if the baby swipes or grabs one of these instruments. I purposely selected rattles which would be easy for tiny fingers to grip, or instruments which don’t take much physical effort to make a sound, be that with their hand, foot, arm or leg. I was careful to ensure that all of my instruments could be easily wiped clean and sterilised after working with each patient, to reduce the risk of infection. Before beginning each music therapy session, I check with the baby’s nurse (and the parent, when they’re present) if it’s okay for me to work with the baby at that time, or whether they’d rather I came back later that day or the following week. It’s important to check that it’s suitable timing, and to be able to be flexible if not. Checking what state the baby is in (whether they are fairly alert, irritable or sleeping) is also important, and determines whether or not I work with them at that moment and, if so, which instruments I would use for that session. Different instruments would be used for different states and clinical goals, and also for different aged babies.

For babies born at very early gestational ages (e.g. 25 weeks), if they’re not many weeks old yet I tend not to work with them. Their mother’s voice will be the best and safest thing for them to listen to, whether that is through talking, humming or singing quietly. It’s crucial not to over-stimulate very young babies, as they need to adjust to the world first, which takes time. The sensory input from bright lights, noises around the ward, smells and touch can be too over-stimulating if they all occur simultaneously. It can calm them just hearing Mum’s voice (and indeed her heartbeat), whilst feeling the vibrations of her voice and heartbeat during skin-to-skin time. With this aged baby, I would only offer emotional support to the parents, and provide suggestions of how they could use humming/gentle lullaby singing, or even just reading or talking to their baby to support their wellbeing and development at that time, being sure to let parents know to watch out for signs of over-stimulation in their baby, explaining what these might be. For babies born at gestational ages such as 34 weeks, I might work with them while their parent is holding them. In this scenario, I would use gentle (and very simple) guitar playing with just two chords, often accompanying improvised quiet singing (e.g. singing “Jacob, Jacob, how are you today?” [don’t worry – no actual patients’ names have been used in this example!]). I try to encourage parents to sing or hum along quietly, but often find that they are perhaps too embarrassed or self-conscious to do so on the ward, which I can completely understand. It’s not the same as being at home and having your own space, with no-one else watching or listening to your every move while you try to get to know your baby. Research has shown the importance of using the mother’s own voice, as this is what the baby will respond to best. The familiar sounds from being in utero (the whooshing of the amniotic fluid, the strong pulse of the mother’s heartbeat and the muffled sounds of the mother’s own voice, as well as those of people she sees regularly – so often the father’s voice is also recognisable to the baby) create a feeling of security for the baby as it tries to adjust to its new surroundings, so re-creating this in an informed and cautious way whilst watching for any signs of over-stimulation is important. During the music therapy session, I’m constantly looking out for any signs of over-stimulation (there are many!) and checking the baby’s monitor for their heart rate, oxygen saturation levels and respiratory rate, which further helps me to assess their mood and current state. I also check the sound levels of my musical interaction via a decibel-monitoring device. With a more relaxed baby comes development, the ability to sleep and feed better and better emotional wellbeing, which is crucial for the often-traumatic environment they now find themselves in. The gato box (see photo – the two-tone wood block) is used to gently re-create sounds of the mother’s heartbeat, and with this you can help the baby to entrain their own heartbeat to a slower pulse, inducing relaxation and often sleep. Using the wave drum (see photo – the oceanic disc, complete with cartoon octopus!) very slowly and quietly (this can take a bit of mastering in itself!) can re-create sounds of the amniotic fluid whooshing around, also helping to calm the baby, reminding them of a time where they felt safe, secure and contained. The music has the power to ‘hold’ them when they are not being physically held, which is also a really effective way of helping them to feel safer. The predictable characteristics of the music, when used in an informed and careful clinical way by a trained music therapist, are purposefully used to help the baby feel more relaxed. When there is a predictableconstant for a period of time (the non-alerting style of the music used), the baby is less likely to become startled by the unpredictablesounds of bins closing, taps running, monitors beeping, doors closing and telephones ringing etc., as they have that predictable sound (the music) to tune into, which provides a sense of security. It’s also important for my sessions to be quite short – often 10 minutes is plenty. I observe for any signs of over-stimulation and bring the session to a close sooner if this occurs. For term babies who are quite alert and aware of their surroundings, perhaps having been on the unit for a while and becoming increasingly bored by the blank white ceiling tiles above them, I work with them in order to increase neuro-development, where sensory stimulation is key. I would most likely use the reflective tambourine (see photo), the easy-grip rattle (see photo) and the wave drum, as well as my guitar and voice. Simple nursery rhymes with lots of repetition can help with early language development. The rattle, wave drum and tambourine are good for visual tracking, and any of these can be used to encourage them to move their arms and legs more, building up their physical development as they reach out to touch them. Music and sounds used can also encourage a baby who usually only looks to one side to explore the other side too, which can be good for their physical development. When the baby touches one of the instruments, it can also teach them about cause and effect, as they learn that when they touch it, it makes that sound. It can also help babies to learn the (unwritten) ‘rules’ of conversation – they make a sound, then I make a sound, then it’s their turn again, then mine, and so on. This can also provide them with a sense of security – the anticipation of knowing whether they will get their turn again, consistently having those needs successfully met, builds trust and a secure attachment, which is important for their future development, and can last long into adulthood. It can be a bit of a balancing act at times, as I have sometimes worked with term babies who have been on the unit for quite some time who need sensory stimulation and a more lively session, yet they’ve been on the same ward as a baby who is only 28 weeks (gestational age) (e.g. in ITU). In this case, I factor in the rest of the babies on that ward, whilst trying to tailor the sessions to the individual baby I’m working with, so ensuring I’m quiet and perhaps sticking more to guitar and singing simple nursery rhymes, or improvised observational singing based on what the baby is doing, whilst slowly moving the rattle from left to right for the baby to track it visually. I often leave them a small square cut from some thin emergency blanket material (bought especially for this purpose) to play with (supervised!) on the days I’m not there – it makes a fascinating crinkly sound and is very cheap, as toys come! After each session I sanitise the musical instruments, then have to negotiate the notes… who knew it could be such a mammoth task adding a new continuation sheet half-way through a patient’s file?! I attend the MDT meeting when possible, where most of the patients are discussed. This helps me to be more informed about the family situation of the babies (including any psycho-social issues), and also helps me to prioritise who to work with (babies andparents). A big part of my clinical work on the NICU, which people may not initially think of, is talking to (and, more importantly, listeningto) parents and providing much-needed emotional support to them. I also ran a music therapy support group for parents, using relaxation techniques and providing a confidential space for them to meet other parents and explore their experiences on the NICU, using music to help in the process. Parents can be experiencing trauma in the NICU, so it’s vital to provide that emotional support, which can be invaluable for helping them cope. Some parents don’t necessarily have much of a support network around them in the form of friends and family, so it’s important for them to have someone to talk to. We have regular confidential clinical supervision and peer supervision, as well as clinical seminars in university. This helps us to think about the work in different ways, which ensures it remains patient-focussed and helps to achieve clinical goals. Reflective practice also plays a big part in our work as music therapists. If you’d like to get more of an idea of how music therapy sessions look in NICU work, you can watch these two short videos on YouTube (though they’re from America, so it’s not exactly the same): https://youtu.be/bwKCK3W-96E https://youtu.be/4qjx2BrrQJg Reading recommendations: Loewy, J., Stewart, K., Dassler, A., Telsey, A. and Homel, P. (2013) The effects of music therapy on vital signs, feeding, and sleep in premature infants. Pediatrics. 131 (5), pp. 902-918. Loewy, J. (2011) Music therapy for hospitalized infants and their parents. In: Edwards, J., ed. (2011) Music Therapy and Parent-Infant Bonding. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 179-190. Shoemark, H., Hanson-Abromeit, D. and Stewart, L., (2015) Constructing optimal experience for the hospitalized newborn through neuro-based music therapy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9: 487.

2 Comments

|

Editors

Dr Annabel Greenwood Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed